In ASP.NET core 2.1 (currently in preview 1) Microsoft have changed the way the ASP.NET core framework is deployed for .NET Core apps, by moving to a system of shared frameworks instead of using the runtime store.

In this post, I look at some of the history and motivation for this change, the changes that you'll see when you install the ASP.NET Core 2.1 SDK or runtime on your machine, and what it all means for you as an ASP.NET Core developer.

If you're not interested in the history side, feel free to skip ahead to the impact on you as an ASP.NET Core developer:

- Referencing the Microsoft.AspNetCore.App metapackage in your apps

- Handling framework version mismatches after deploying your app

- Ensuring you don't accidentally pull in an unsupported framework package version

The Microsoft.AspNetCore.All metapackage and the runtime store

In this section, I'll recap over some of the problems that the Microsoft.AspNetCore.All was introduced to solve, as well as some of the issues it introduces. This is entirely based on my own understanding of the situation (primarily gleaned from these GitHub issues), so do let me know in the comments if I've got anything wrong or misrepresented the situation!

In the beginning, there were packages. So many packages.

With ASP.NET Core 1.0, Microsoft set out to create a highly modular, layered, framework. Instead of the monolithic .NET framework that you had to install in it's entirety in a central location, you could reference individual packages that provide small, discrete piece of functionality. Want to configure your app using JSON files? Add the Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.Json package. Need environment variables? That's a different package (Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.EnvironmentVariables).

This approach has many benefits, for example:

- You get a clear "layering" of dependencies

- You can update packages independently of others

- You only have to include the packages that you actually need, reducing the published size of your app.

Unfortunately, these benefits diminished as the framework evolved.

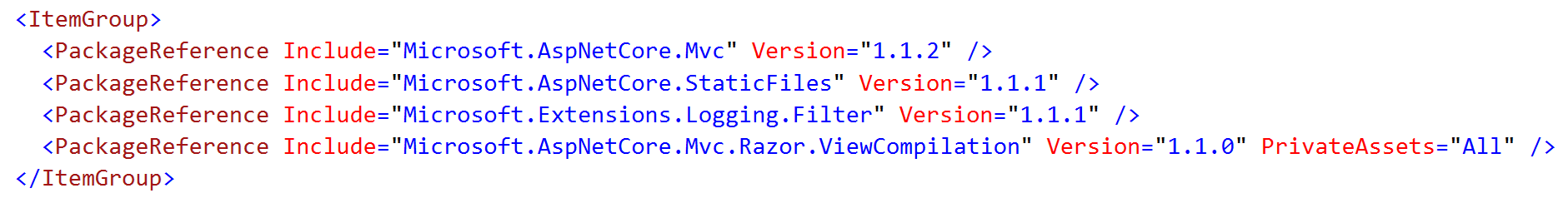

Initially, all the framework packages started at version 1.0.0, and it was simply a case of adding or removing packages as necessary for the required functionality. But bug fixes arrived shortly after release, and individual packages evolved at different rates. Suddenly .csproj files were awash with different version numbers, 1.0.1, 1.0.3, 1.0.2. It was no longer easy to tell at a glance whether you were on the latest version of a package, and version management became a significant chore. The same was true when ASP.NET Core 1.1 was released - a brief consolidation was followed by diverging package versions:

On top of that, the combinatorial problem of testing every version of a package with every other version, meant that there was only one "correct" combination of versions that Microsoft would support. For example, using the 1.1.0 version of the StaticFiles middleware with the 1.0.0 MVC middleware was easy to do, and would likely work without issue, but was not a configuration Microsoft could support.

It's worth noting that the Microsoft.AspNetCore metapackage partially solved this issue, but it only included a limited number of packages, so you would often still be left with a degree of external consolidation required.

Add to that the discoverability problem of finding the specific package that contains a given API, slow NuGet restore times due to the sheer number of packages, and a large published output size (as all packages are copied to the bin folder) and it was clear a different approach was required.

Unifying package versions with a metapackage

In ASP.NET Core 2.0, Microsoft introduced the Microsoft.AspNetCore.All metapackage and the .NET Core runtime store. These two pieces were designed to workaround many of the problems that we've touched on, without sacrificing the ability to have distinct package dependency layers and a well factored framework.

I discussed this metapackage and the runtime store in a previous post, but I'll recap here for convenience.

The Microsoft.AspNetCore.All metapackage solves the issue of discoverability and inconsistent version numbers by including a reference to every package that is part of ASP.NET Core 2.0, as well as third-party packages referenced by ASP.NET Core. This includes both integral packages like Newtonsoft.Json, but also packages like StackExchange.Redis that are used by somewhat-peripheral packages like Microsoft.Extensions.Caching.Redis.

On the face of it, you might expect shipping a larger metapackage to cause everything to get even slower - there would be more packages to restore, and a huge number of packages in your app's published output.

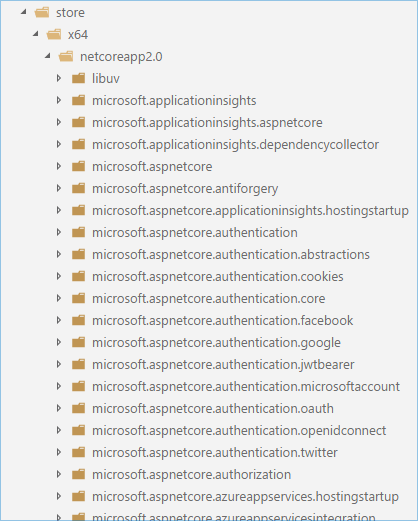

However, .NET Core 2.0 includes a new feature called the runtime store. This essentially lets you pre-install packages on a machine, in a central location, so you don't have to include them in the publish output of your individual apps. When you install the .NET Core 2.0 runtime, all the packages required by the Microsoft.AspNetCore.All metapackage are installed globally (at C:\Program Files\dotnet\store. on Windows):

When you publish your app, the Microsoft.AspNetCore.All metapackage trims out all the dependencies that it knows will be in the runtime store, significantly reducing the number of dlls in your published app's folder.

The runtime store has some additional benefits. It can use "ngen-ed" libraries that are already optimised for the the target machine, improving start up time. You can also use the store to "light-up" features at runtime such as Application insights, but you can create your own manifests too.

Unfortunately, there are a few downsides to the store...

The ever-growing runtime stores

By design, if your app is built using the Microsoft.AspNetCore.All metapacakge, and hence uses the runtime store output-trimming, you can only run your app on a machine that has the correct version of the runtime store installed (via the .NET Core runtime installer).

For example, if you use the Microsoft.AspNetCore.All metapackage for version 2.0.1, you must have the runtime store for 2.0.1 installed, version 2.0.0 and 2.0.2 are no good. That means if you need to fix a critical bug in production, you would need to install the next version of the runtime store, and you would need to update, recompile, and republish all of your apps to use it. This generally leads to runtime stores growing, as you can't easily delete old versions.

This problem is a particular issue if you're running a platform like Azure, so Microsoft are acutely aware of the issue. If you deploy your apps using Docker for example, this doesn't seem like as big of a problem.

The solution Microsoft have settled on is somewhat conceptually similar to the runtime store, but it actually goes deeper than that.

Introducing Shared Frameworks in ASP.NET Core 2.1

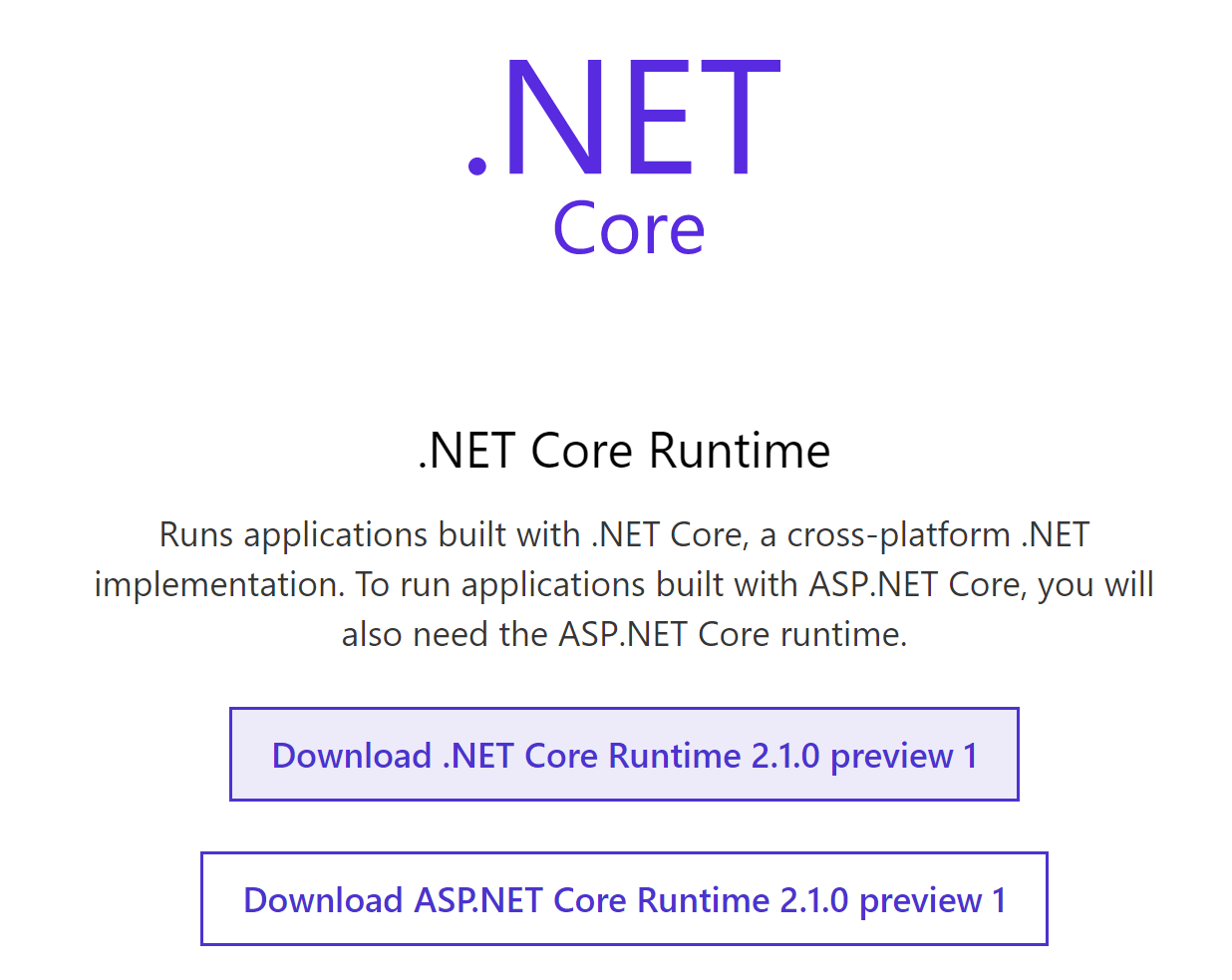

In ASP.NET Core 2.1 (currently at preview 1), ASP.NET Core is now a Shared Framework, very similar to the existing Microsoft.NETCore.App shared framework that effectively "is" .NET Core. When you install the .NET Core runtime you can also install the ASP.NET Core runtime:

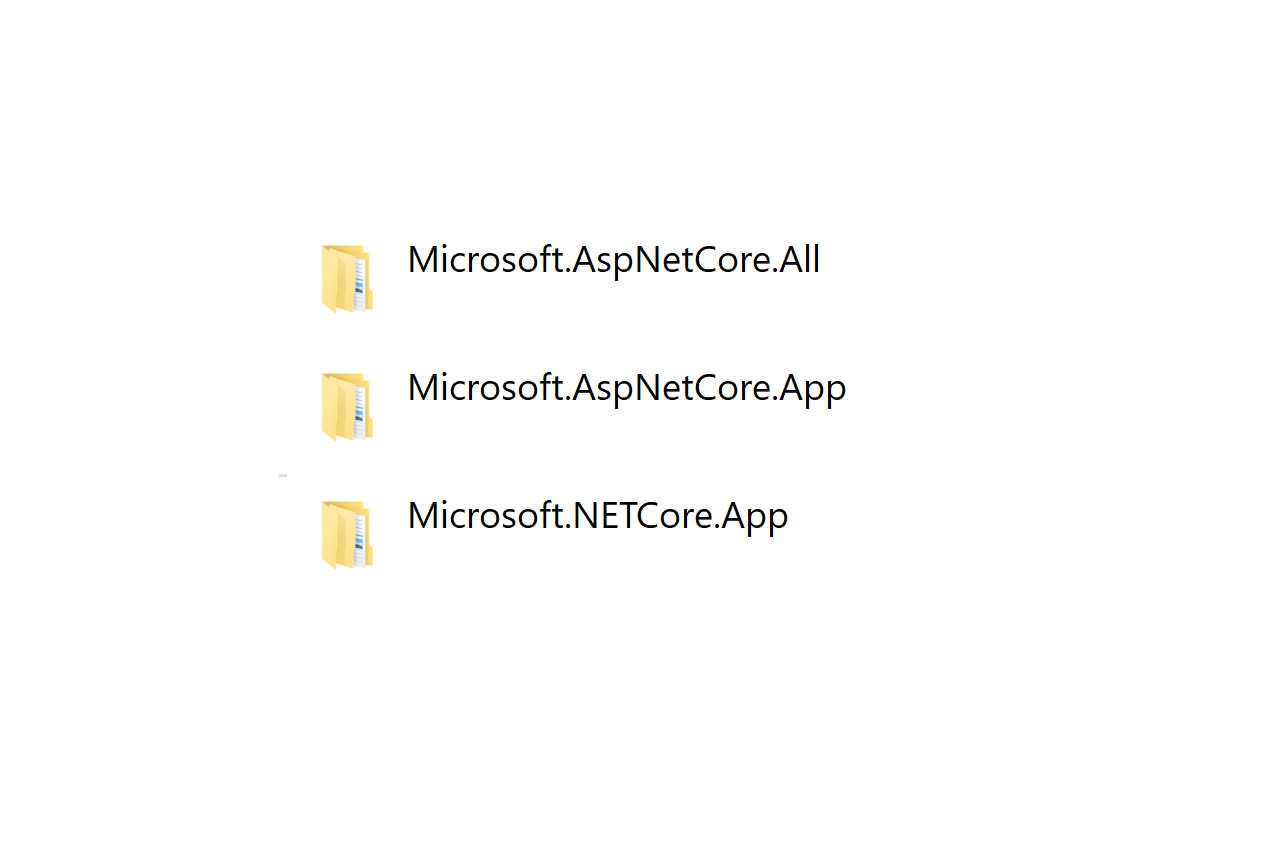

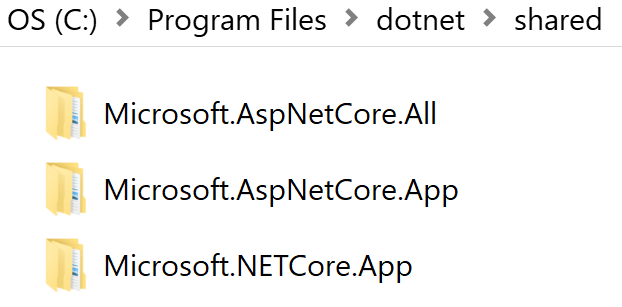

After you install the preview, you'll find you have three folders in C:\Program Files\dotnet\shared (on Windows):

These are the three Shared frameworks for ASP.NET Core 2.1:

- Microsoft.NETCore.App - the .NET Core framework that previously was the only framework installed

- Microsoft.AspNetCore.App - all the dlls from packages that make up the "core" of ASP.NET Core, with as many packages that have third-party dependencies removed

- Microsoft.AspNetCore.All - all the packages that were previously referenced by the Microsoft.AspNetCore.All metapackage, including all their dependencies.

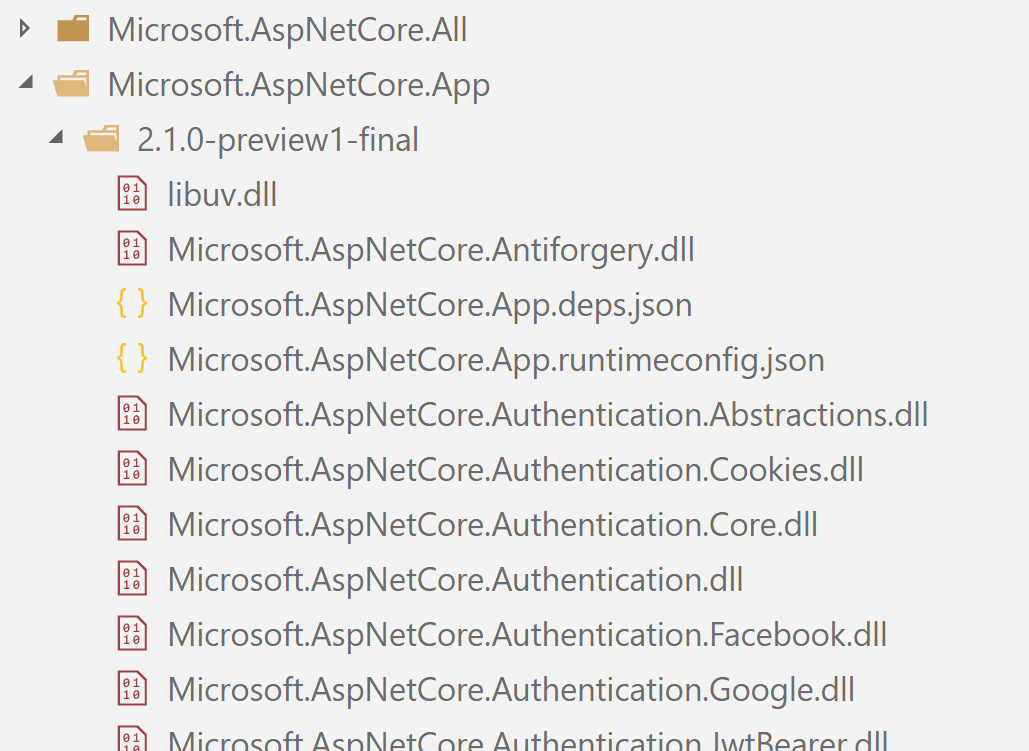

Each of these frameworks "inherits" from the last, so there's no duplication of libraries between them, but the folder layout is much simpler - just a flat list of libraries:

So why should I care?

That's all nice and interesting, but how does it affect how we develop ASP.NET Core applications? Well for the most part, things are much the same, but there's a few points to take note of.

Reference Microsoft.AspNetCore.App in your apps

As described in this issue, Microsoft have introduced another metapackage called Microsoft.AspNetCore.App with ASP.NET Core 2.1. This contains all of the libraries that make up the core of ASP.NET Core that are shipped by the .NET and ASP.NET team themselves. Microsoft recommend using this package instead of the All metapackage, as that way they can provide direct support, instead of potentially having to rely on third-party libraries (like StackExchange.Redis or SQLite).

In terms of behaviour, you'll still effectively get the same publish output dependency-trimming that you do currently (though the mechanism is slightly different), so there's no need to worry about that. If you need some of the extra packages that aren't part of the new Microsoft.AspNetCore.App metapackage, then you can just reference them individually.

Note that you are still free to reference the Microsoft.AspNetCore.All metapackage, it's just not recommended as it locks you into specific versions of third-party dependencies. As you saw previously, the All shared framework inherits from the App shared framework, so it should be easy enough to switch between them

Framework version mismatches

By moving away from the runtime store, and instead moving to a shared-framework approach, it's easier for the .NET Core runtime to handle mis-matches between the requested runtime and the installed runtimes.

With ASP.NET Core prior to 2.1, the runtime would automatically roll-forward patch versions if a newer version of the runtime was installed on the machine, but it would never roll forward minor versions. For example, if versions 2.0.2 and 2.0.3 were installed, then an app targeting 2.0.2 would use 2.0.3 automatically. However if only version 2.1.0 was installed and the app targeted version 2.0.0, the app would fail to start.

With ASP.NET Core 2.1, the runtime can roll-forward by using a newer minor version of the framework than requested. So in the previous example, an app targeting 2.0.0 would be able to run on a machine that only has 2.1.0 or 2.2.1 installed for example.

An exact minor match is always chosen preferentially; the minor version only rolls-forward when your app would otherwise be unable to run.

Exact dependency ranges

The final major change introduced in Microsoft.AspNetCore.App is the use of exact-version requirements for referenced NuGet packages. Typically, most NuGet packages specify their dependencies using "at least" ranges, where any dependent package will satisfy the requirement.

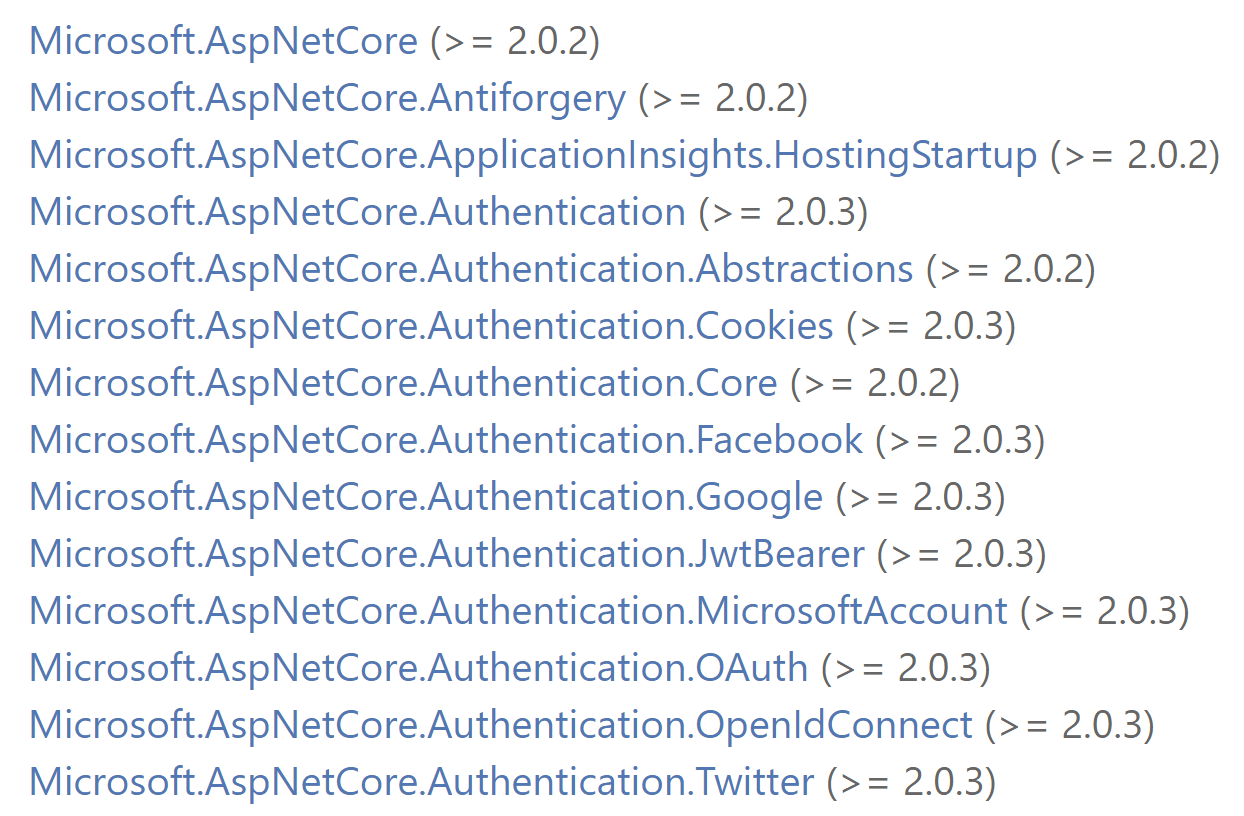

For example, the image below shows some of the dependencies of the Microsoft.AspNetCore.All (version 2.0.6) package.

Due to the way these dependencies are specified, it would be possible to silently "lift" a dependency to a higher version than that specified. For example, if you added a package which depended on a newer version, say 2.1.0 of Microsoft.AspNetCore.Authentication, to an app using version 2.0.0 of the All package then NuGet would select 2.1.0 as it satisfies all the requirements. That could result in you trying to use using untested combinations of the ASP.NET Core framework libraries.

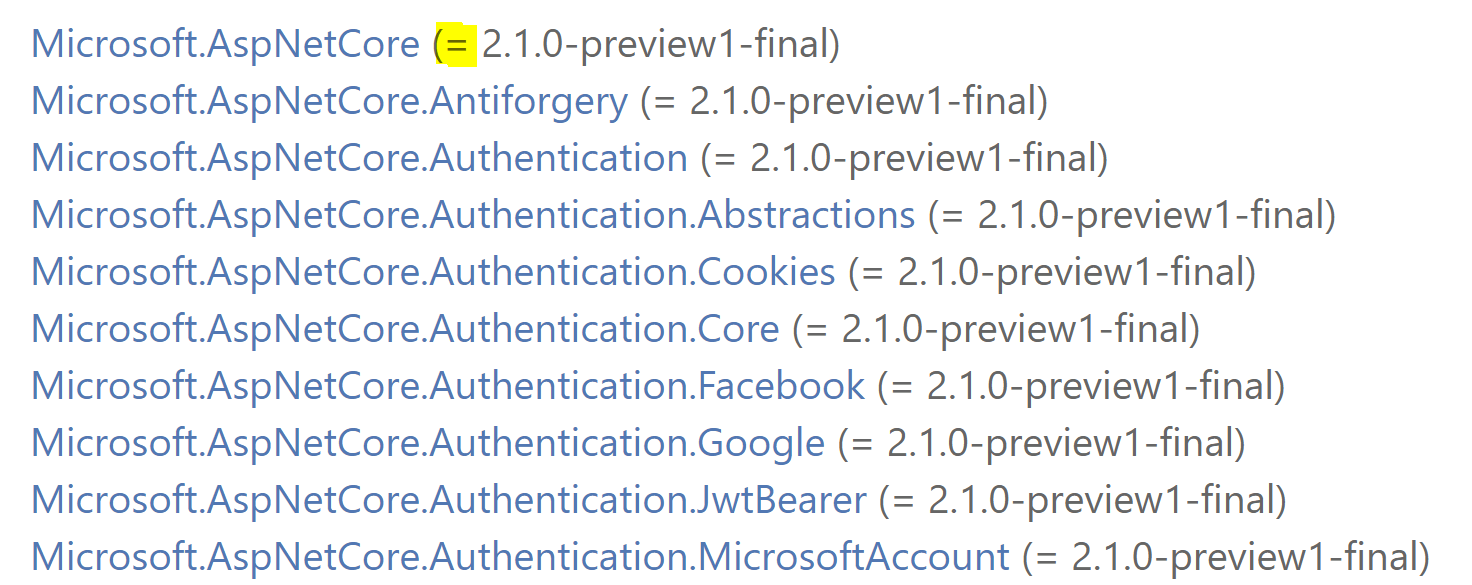

Consequently, the Microsoft.AspNetCore.App package specifies exact versions for it's dependencies (note the = instead of >=)

Now if you attempt to pull in a higher version of a framework library transitively, you'll get an error from NuGet when it tries to restore, warning you about the issue. So if you attempt to use version 2.2.0 of Microsoft.AspNetCore.Antiforgery with version 2.1.0 of the App metapackage for example, you'll get an error.

It's still possible to pull in a higher version of a framework package if you need to, by referencing it directly and overriding the error, but at that point you're making a conscious decision to head into uncharted waters!

Summary

ASP.NET Core 2.1 brings a surprising number of fundamental changes under the hood for a minor release, and fundamentally re-architects the way ASP.NET Core apps are delivered. However as a developer you don't have much to worry about. Other than switching to the Microsoft.AspNetCore.App metapackage and making some minor adjustments, the upgrade from 2.0 to 2.1 should be very smooth. If you're interested in digging further into the under-the-hood changes, I recommend checking out the links below: