There's a new "default" way to build applications in .NET, using WebApplication.CreateBuilder(). In this post I compare this approach to the previous approaches, discuss why the change was made, and look at the impact. In the next post I'll look at the code behind WebApplication and WebApplicationBuilder to see how they work.

Building ASP.NET Core applications: a history lesson

Before we look at .NET 6, I think it's worthwhile looking at how the "bootstrap" process of ASP.NET Core apps has evolved over the last few years, as the initial designs had a huge impact on where we are today. That will become even more apparent when we look at the code behind WebApplicationBuilder in the next post!

Even if we ignore .NET Core 1.x (which is completely unsupported at this point), we have three different paradigms for configuring an ASP.NET Core application:

WebHost.CreateDefaultBuilder(): the "original" approach to configuring an ASP.NET Core app, as of ASP.NET Core 2.x.Host.CreateDefaultBuilder(): a re-building of ASP.NET Core on top of the genericHost, supporting other workloads like Worker services. The default approach in .NET Core 3.x and .NET 5.WebApplication.CreateBuilder(): the new hotness in .NET 6.

To get a better feel for the differences, I've reproduced the typical "startup" code in the following sections, which should make the changes in .NET 6 more apparent.

ASP.NET Core 2.x: WebHost.CreateDefaultBuilder()

In the first version of ASP.NET Core 1.x, (if I remember correctly) there was no concept of a "default" host. One of the ideologies of ASP.NET Core is that everything should be "pay for play" i.e. if you don't need to use it, you shouldn't pay the cost for the feature being there.

In practice, that meant the "getting started" template contained a lot of boilerplate, and a lot of NuGet packages. To counteract the shock of seeing all that code just to get started, ASP.NET Core introduced WebHost.CreateDefaultBuilder(). This sets up a whole load of defaults for you, creating an IWebHostBuilder, and building an IWebHost.

I looked into the code of

WebHost.CreateDefaultBuilder()back in 2017 and compared it to ASP.NET Core 1.x, in case you feel like a trip down memory lane.

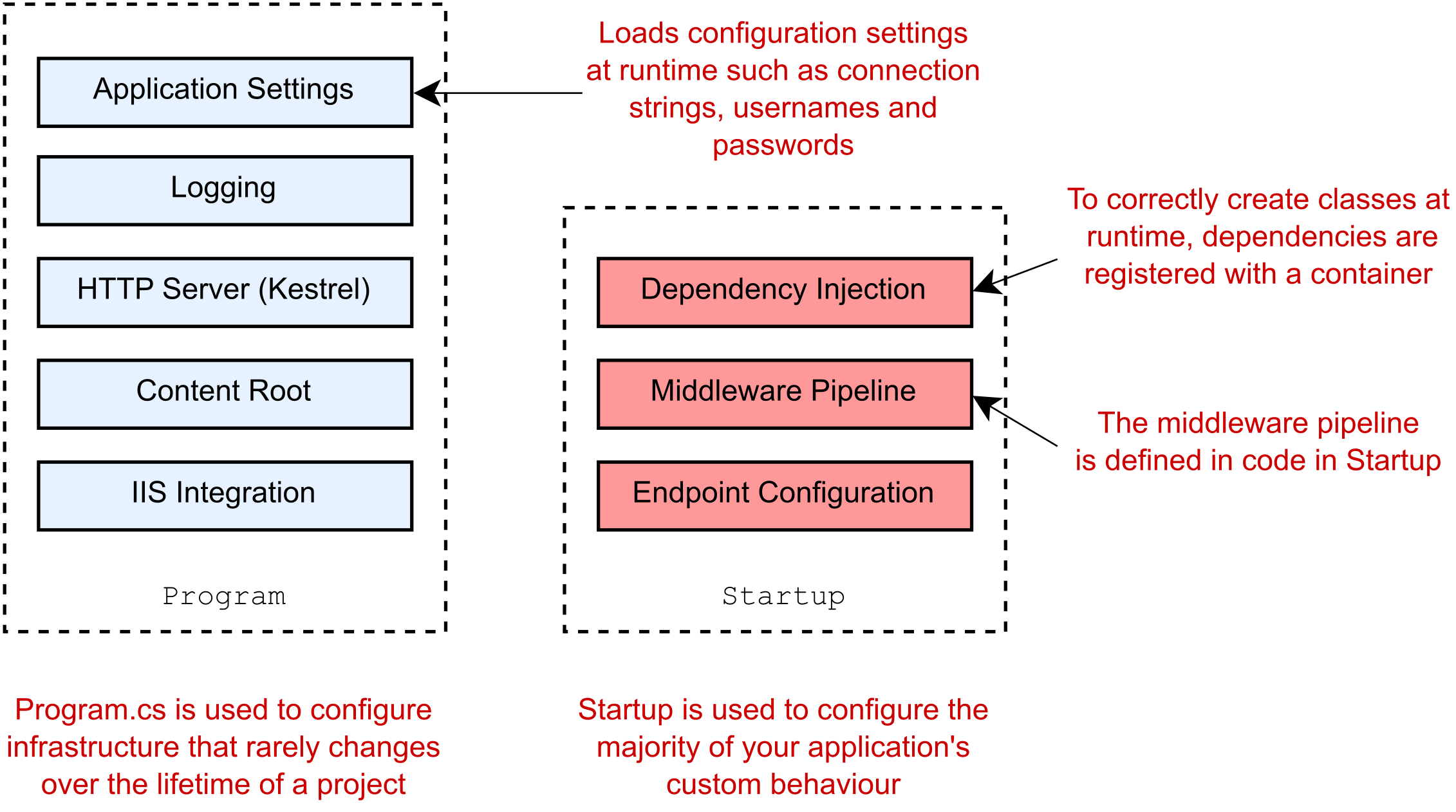

Right from the start, ASP.NET Core has separated "host" bootstrapping, from your "application" bootstrapping. Historically, this manifests as splitting your startup code between two files, traditionally called Program.cs and Startup.cs.

In ASP.NET Core 2.1, Program.cs calls WebHost.CreateDefaultBuilder(), which sets up your application configuration (loading from appsettings.json for example), logging, and configures Kestrel and/or IIS integration.

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

BuildWebHost(args).Run();

}

public static IWebHost BuildWebHost(string[] args) =>

WebHost.CreateDefaultBuilder(args)

.UseStartup<Startup>()

.Build();

}

The default templates also reference a Startup class. This class doesn't implement an interface explicitly. Rather the IWebHostBuilder implementation knows to look for ConfigureServices() and Configure() methods to set up your dependency injection container and middleware pipeline respectively.

public class Startup

{

public Startup(IConfiguration configuration)

{

Configuration = configuration;

}

public IConfiguration Configuration { get; }

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddMvc();

}

// This method gets called by the runtime. Use this method to configure the HTTP request pipeline.

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IHostingEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

app.UseStaticFiles();

app.UseMvc(routes =>

{

routes.MapRoute(

name: "default",

template: "{controller=Home}/{action=Index}/{id?}");

});

}

}

In the Startup class above, we added the MVC services to the container, added the exception handling and static files middleware, and then added the MVC middleware. The MVC middleware was the only real practical way to build applications initially, catering for both server rendered views and RESTful API endpoints.

ASP.NET Core 3.x/5: the generic HostBuilder

ASP.NET Core 3.x brought some big changes to the startup code for ASP.NET Core. Previously, ASP.NET Core could only really be used for web/HTTP workloads, but in .NET Core 3.x a move was made to support other approaches: long running "worker services" (for consuming message queues, for example), gRPC services, Windows Services, and more. The goal was to share the base framework that was built specifically for building web apps (configuration, logging, DI)with these other app types.

The upshot was the creation of a "Generic Host" (as opposed to the Web Host), and a "re-platforming" of the ASP.NET Core stack on top of it. Instead of an IWebHostBuilder, there was an IHostBuilder.

Again, I have a contemporaneous series of posts about this migration if you're interested!

This change caused a few inevitable breaking changes, but the ASP.NET team did their best to provide routes for all that code written against IWebHostBuilder rather than IHostBuilder. One such workaround was the ConfigureWebHostDefaults() method used by default in the Program.cs templates:

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

CreateHostBuilder(args).Build().Run();

}

public static IHostBuilder CreateHostBuilder(string[] args) =>

Host.CreateDefaultBuilder(args)

.ConfigureWebHostDefaults(webBuilder =>

{

webBuilder.UseStartup<Startup>();

};

}

}

The need for ConfigureWebHostDefaults to register the Startup class of ASP.NET Core apps demonstrates one of the challenges for the .NET team in providing a migration path from IWebHostBuilder to IHostBuilder. Startup is inextricably tied to web apps, as the Configure() method is about configuring middleware. But worker services and many other apps don't have middleware, so it doesn't make sense for Startup classes to be a "generic host" level concept.

This is where the ConfigureWebHostDefaults() extension method on IHostBuilder comes in. This method wraps the IHostBuilder in an internal class, GenericWebHostBuilder, and sets up all the defaults that WebHost.CreateDefaultBuilder() did in ASP.NET Core 2.1. GenericWebHostBuilder acts as an adapter between the old IWebHostBuilder and the new IHostBuilder.

Another big change in ASP.NET Core 3.x was the introduction of endpoint routing. Endpoint routing was one of the first attempts to make concepts available that were previously limited to the MVC portion of ASP.NET Core, in this case, the concept of routing. This required some rethinking of your middleware pipeline, but in many cases the necessary changes were minimal.

Despite these changes, the Startup class in ASP.NET Core 3.x looked pretty similar to the 2.x version. The example below is almost equivalent to the 2.x version (though I've switched to Razor Pages instead of MVC).

public class Startup

{

public Startup(IConfiguration configuration)

{

Configuration = configuration;

}

public IConfiguration Configuration { get; }

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddRazorPages();

}

// This method gets called by the runtime. Use this method to configure the HTTP request pipeline.

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

app.UseStaticFiles();

app.UseRouting();

app.UseAuthorization();

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints =>

{

endpoints.MapRazorPages();

});

}

}

ASP.NET Core 5 brought relatively few big changes to existing applications, such that upgrading from 3.x to 5 was generally as simple as changing the target framework and updating some NuGet packages 🎉

For .NET 6 that will hopefully still be true if you're upgrading existing applications. But for new apps, the default bootstrapping experience has completely changed…

ASP.NET Core 6: WebApplicationBuilder:

All the previous versions of ASP.NET Core have split configuration across 2 files. In .NET 6, a raft of changes, to C#, to the BCL, and to ASP.NET Core, mean that now everything can be in a single file.

Note that nothing forces you to use this style. All the code I showed in the ASP.NET Core 3.x/5 code still works in .NET 6!

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddRazorPages();

var app = builder.Build();

if (app.Environment.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

app.UseStaticFiles();

app.MapGet("/", () => "Hello World!");

app.MapRazorPages();

app.Run();

There's so many changes here, but some of the most obvious are:

- Top level statements means no

Program.Main()boilerplate. - Implicit using directives means no using statements are required. I didn't include them in the snippets for previous versions, but there are none required for .NET 6!

- No

Startupclass - everything is in one file.

It's obviously a lot less code, but is it necessary? Is it just churn for the sake of churn? And how does it work?

Where did all the code go?

One of the big focuses of .NET 6 has been on the "newcomer" point of view. As a beginner to ASP.NET Core, there's a whole load of concepts you have to get your head around really quickly. Just take a look at the table of contents for my book; there's a lot to get your head around!

The changes in .NET 6 are heavily focused on removing the "ceremony" associated with getting started, and hide concepts that can be confusing to newcomers. For example:

usingstatements aren't necessary when getting started. Although tooling usually makes these a non-issue in practice, they are clearly an unnecessary concept when you're getting started.- Similarly to this the

namespaceis an unnecessary concept when you get started Program.Main()… why's it called that? Why do I need it? Because you do. Except now you don't.- Configuration isn't split between two files, Program.cs and Startup.cs. While I liked that "separation of concerns", I won't miss explaining why the split is the way it is to newcomers.

- While we're talking about

Startup, we no longer have to explain "magic" methods, that can be called even though they don't explicitly implement an interface.

In addition, we have the new WebApplication and WebApplicationBuilder types. These types weren't strictly necessary to achieve the above goals, but they do make for a somewhat "cleaner" configuration experience.

Do we really need a new type?

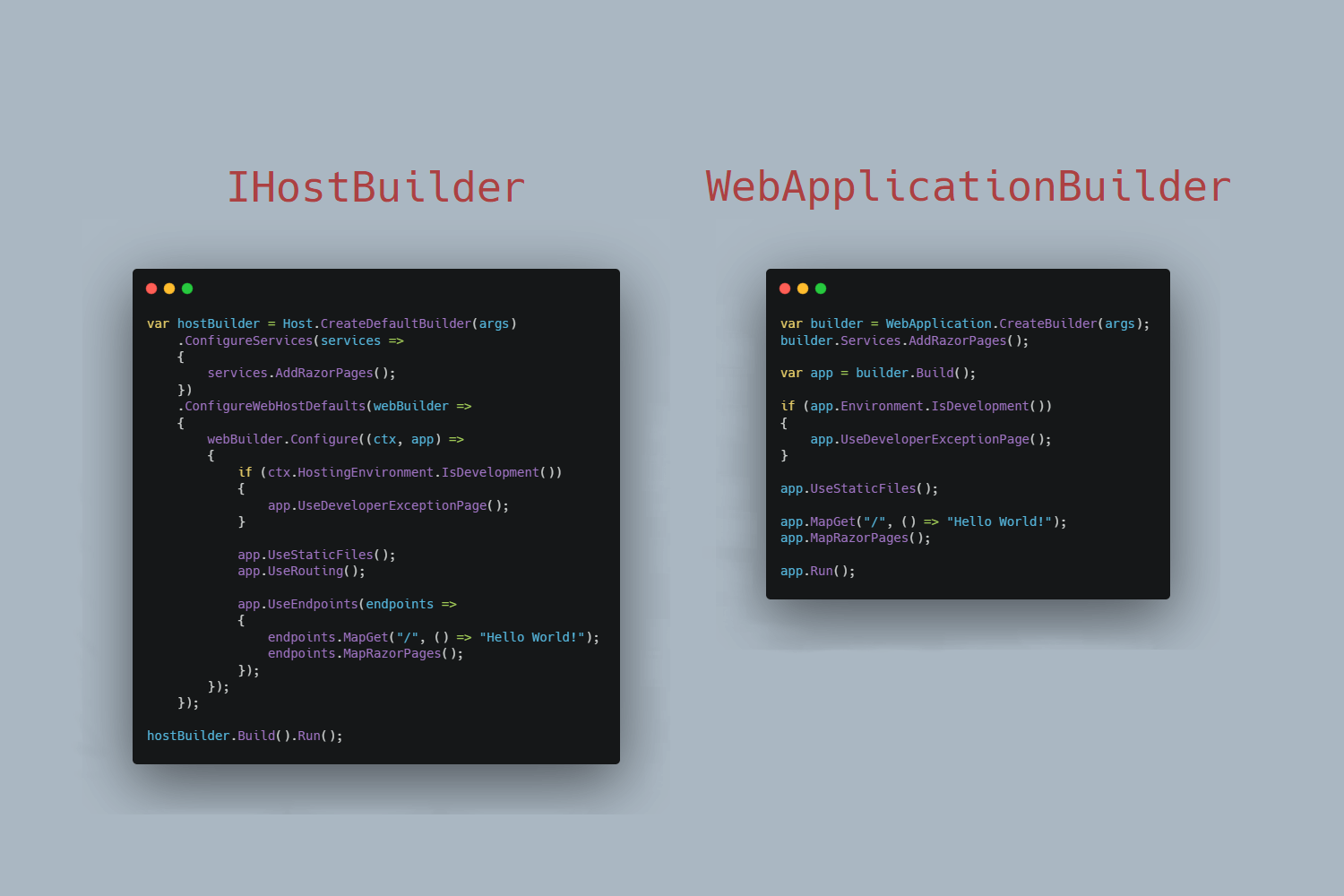

Well, no, we don't need it. We can write a .NET 6 app that's very similar to the above sample using the generic host instead:

var hostBuilder = Host.CreateDefaultBuilder(args)

.ConfigureServices(services =>

{

services.AddRazorPages();

})

.ConfigureWebHostDefaults(webBuilder =>

{

webBuilder.Configure((ctx, app) =>

{

if (ctx.HostingEnvironment.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

app.UseStaticFiles();

app.UseRouting();

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints =>

{

endpoints.MapGet("/", () => "Hello World!");

endpoints.MapRazorPages();

});

});

});

hostBuilder.Build().Run();

I think you have to agree though, that looks a lot more complicated than the .NET 6 WebApplication version. We have a whole bunch of nested lambdas, you have to make sure you get the right overloads so that you can access configuration (for example), and generally speaking it turns what is a (mostly) procedural bootstrapping script into something for more complex.

Another benefit of the

WebApplicationBuilderis thatasynccode during startup is a lot simpler. You can just callasyncmethods whenever you like. That should hopefully make this series I wrote on doing this in ASP.NET Core 3.x/5 obsolete!

The neat thing about WebApplicationBuilder and WebApplication is that they're essentially equivalent to the above generic host setup, but they do it with an arguably simpler API.

Most configuration happens in WebApplicationBuilder

Lets start by looking at WebApplicationBuilder.

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddRazorPages();

WebApplicationBuilder is responsible for 4 main things:

- Adding Configuration using

builder.Configuration. - Adding Services using

builder.Services - Configure Logging using

builder.Logging - General

IHostBuilderandIWebHostBuilderconfiguration

Taking each of those in turn…

WebApplicationBuilder exposes the ConfigurationManager type for adding new configuration sources, as well as accessing configuration values, as I described in my previous post.

It also exposes an IServiceCollection directly for adding services to the DI container. So whereas with the generic host you had to do

var hostBuilder = Host.CreateDefaultBuilder(args);

hostBuilder.ConfigureServices(services =>

{

services.AddRazorPages();

services.AddSingleton<MyThingy>();

})

with WebApplicationBuilder you can do

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddRazorPages();

builder.Services.AddSingleton<MyThingy>();

Similarly, for logging, instead of doing

var hostBuilder = Host.CreateDefaultBuilder(args);

hostBuilder.ConfigureLogging(builder =>

{

builder.AddFile();

})

you would do:

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Logging.AddFile();

This has exactly the same behaviour, just in an easier-to-use API. For those extension points that rely on IHostBuilder or IWebHostBuilder directly, WebApplicationBuilder exposes the properties Host and WebHost respectively.

For example, Serilog's ASP.NET Core integration hooks into the IHostBuilder, so in ASP.NET Core 3.x/5 you would add it using the following:

public static IHostBuilder CreateHostBuilder(string[] args) =>

Host.CreateDefaultBuilder(args)

.UseSerilog() // <-- Add this line

.ConfigureWebHostDefaults(webBuilder =>

{

webBuilder.UseStartup<Startup>();

});

With WebApplicationBuilder, you would make the UseSerilog() call on the Host property, instead of on the builder itself:

builder.Host.UseSerilog();

In fact, WebApplicationBuilder is where you do all your configuration except the middleware pipeline.

WebApplication wears many hats

Once you've configured everything you need to on WebApplicationBuilder you call Build() to create an instance of WebApplication:

var app = builder.Build();

WebApplication is interesting as it implements multiple different interfaces:

IHost- used to start and stop the hostIApplicationBuilder- used to build the middleware pipelineIEndpointRouteBuilder- used to add endpoints

Those latter two points are very much related. In ASP.NET Core 3.x and 5, the IEndpointRouteBuilder is used to add endpoints by calling UseEndpoints() and passing a lambda to it, for example:

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app)

{

app.UseStaticFiles();

app.UseRouting();

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints =>

{

endpoints.MapRazorPages();

});

}

There's a few complexities to this .NET 3.x/5 pattern for people new to ASP.NET Core:

- The middleware pipeline building occurs in the

Configure()function inStartup(you have to know to look there) - You have to make sure to call

app.UseRouting()beforeapp.UseEndpoints()(as well as place other middleware in the right place) - You have to use a lambda to configure the endpoints (not complicated for users familiar to C#, but could be confusing to newcomers)

WebApplication significantly simplifies this pattern:

app.UseStaticFiles();

app.MapRazorPages();

This is clearly much simpler, though I found it a bit confusing as the distinction between middleware and endpoints is far less clear than in .NET 5.x etc. That's probably just a taste thing, but I think it muddies the "order is important" message (which applies to middleware, but not endpoints generally).

What I haven't shown yet is the nuts and bolts of how WebApplication and WebApplicationBuilder are built. In the next post I'll peel back the curtain so we can see what's really going on behind the scenes.

Summary

In this post I described how the bootstrapping of ASP.NET Core apps has changed from version 2.x all the way up to .NET 6. I show the new WebApplication and WebApplicationBuilder types introduced in .NET 6, discuss why they were introduced, and some of the advantages they bring. Finally I discuss the different roles the two classes play, and how their APIs make for a simpler start up experience. In the next post, I'll look at some of the code behind the types to see how they work.